Anaphylaxis in the Backcountry: What Every WFR/WEMT Needs to Know

Wilderness anaphylaxis assessment and treatment. WFR and WEMT epinephrine administration wilderness protocols and guidelines.

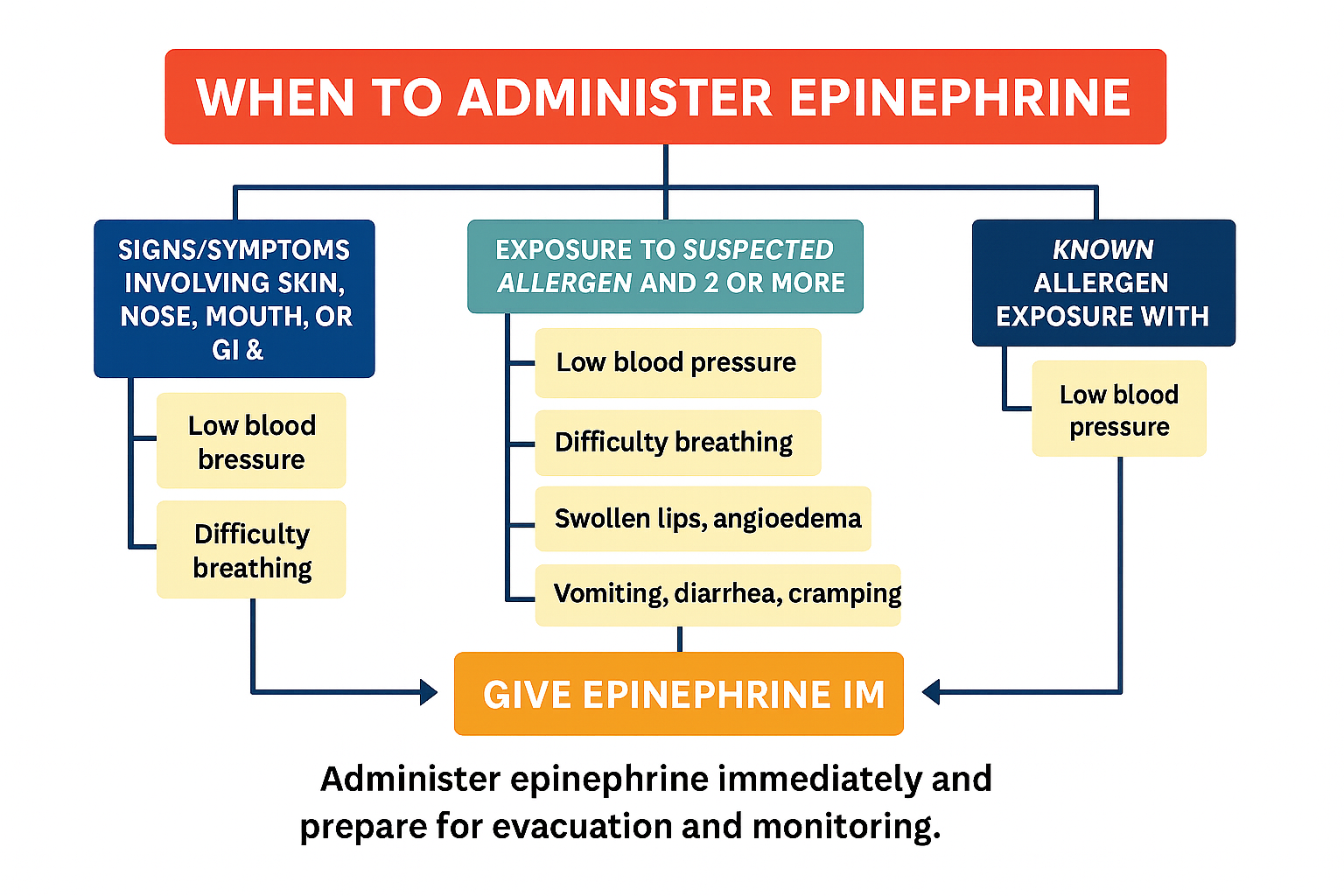

As WFRs, WEMTs, SAR techs, and guides with medical training, we know the backcountry doesn’t play by the rules of a hospital or clinic. When someone goes into anaphylaxis deep in the woods, minutes matter and resources are limited. That’s why I wanted to share a clear, practical overview of the latest Wilderness Medical Society clinical practice guidelines and other recent research papers on anaphylaxis to provide you with evidence-based clinical guidelines for wilderness applications[1]. I also thought it was important to revisit this topic because I still frequently see wilderness first responders and wilderness EMTs unsure or hesitant about when to administer epinephrine for anaphylaxis.

This post is a summary focused on what you really need to know in the field — from recognizing the emergency to delivering life-saving epinephrine and deciding when and how to evacuate. I’ll break down the essentials, share some real-world insights, and keep it pragmatic, because when you’re out there, it’s all about timely, effective action.

Quick Refresher: What Is Anaphylaxis and Why Should We Care?

Anaphylaxis is a rapid, severe allergic reaction that can cause airway swelling, respiratory distress, sudden drops in blood pressure, and shock. Without quick treatment, it can progress to life-threatening cardiovascular collapse. Around 1.6–2% of people in the U.S. are at risk, and wilderness programs like NOLS and Outward Bound show this is a real threat even in remote environments[1][2][3]. Notably, over 20% of anaphylaxis cases in participants and guides within these programs occurred in individuals without any prior history of allergies or anaphylaxis, highlighting how unpredictable this condition can be and why every wilderness responder must be prepared to act even when no allergy history exists[1].

The reaction happens when mast cells and basophils release large amounts of histamine and other mediators like leukotrienes and prostaglandins. These chemicals cause blood vessels to become leaky, leading to fluid loss and swelling; they also narrow the airways and decrease heart function. Together, these effects cause anaphylactic shock—a combination of respiratory distress and low blood pressure that can quickly lead to cardiovascular collapse and cardiac arrest if not treated immediately. Understanding this helps explain why rapid epinephrine administration is critical in the field[1].

Spotting Anaphylaxis: More Than Just a Rash

Most of us learned to look for hives and swelling as the telltale signs, but anaphylaxis can be sneaky. Roughly 10-20% of cases come without skin symptoms — no rash, no itching. So, if someone’s having sudden breathing trouble, dizziness, vomiting, or throat tightness after eating, being stung, or even after exercise, treat it like anaphylaxis until proven otherwise[1][6].

Unfortunately, prehospital care studies show that many EMS providers hesitate or delay epinephrine administration, especially in pediatric patients. One study found only about 54% of pediatric patients with clear anaphylaxis indications received epinephrine from EMS or prior to EMS arrival, with younger children under 10 at higher risk of not receiving treatment[4][7]. This underlines the importance of decisiveness in the field — epinephrine saves lives and should never be delayed.

Keep in mind biphasic reactions — where symptoms disappear but then come back hours later. Studies show this can happen in up to 6% of cases, which means observation and monitoring after treatment is critical[1].

Assessing Anaphylaxis in the Field: A Practical Approach

Step one is always scene safety. No point treating anaphylaxis if you get stung or exposed yourself. Then move quickly into your primary survey — assess airway patency, listen for abnormal breath sounds like wheezing or stridor, check respiratory effort, palpate pulses, and monitor for signs of hypotension such as dizziness, altered mental status, or weakness.

Gather history about recent exposure to likely allergens — foods, insect stings, medications, or even exercise (exercise-induced anaphylaxis does occur in the backcountry). Watch closely for red flags like upper airway swelling, hoarseness, or sudden loss of consciousness.

When in doubt, treat. Early recognition and intervention save lives.

Epinephrine: The Backcountry Lifesaver

There’s no substitute for timely epinephrine. It’s the only medication proven to reverse the cascade of allergic chemicals causing the reaction. Importantly, there are no absolute contraindications to administering epinephrine in anaphylaxis, so don’t hesitate to give it when indicated. The Wilderness Medical Society guidelines emphasize: Give epinephrine IM in the anterolateral thigh as soon as anaphylaxis is suspected — no delays, no second-guessing[1][8].

How Much and How Often?

Adults: 0.3 to 0.5 mg IM

Kids: 0.01 mg/kg IM, commonly 0.15 mg for small children

Repeat doses every 5 to 15 minutes if symptoms persist[1].

For intramuscular epinephrine administration in the wilderness, the preferred anatomical site is the anterolateral thigh due to its rich vascular supply and consistent muscle mass, which allows for rapid absorption; the secondary site is the deltoid muscle, used only when thigh access is not feasible, though it has less muscle mass and may result in slower absorption, making the thigh the optimal choice for timely treatment of anaphylaxis【1】【7】.

Delivery Options in the Field

Autoinjectors (EpiPens, Auvi-Q, etc.): Quick, simple, but pricey and require regular practice to avoid mishaps. Needle length may not always reach muscle in larger patients but generally effective[9].

Syringe and vial method (“Check and Inject”): Some EMS systems have implemented formal training programs teaching EMTs to safely draw epinephrine from vials and inject IM, with high protocol adherence and no major safety concerns reported[7][10]. This is a cost-effective alternative that WFRs and WEMTs with the appropriate training may consider to have more available epinephrine for larger groups in a smaller, compact, affordable package without sacrificing patient care quality.

Remember: EPI first, EPI fast.

When the First Dose Isn’t Enough: Managing Refractory Anaphylaxis

Sometimes, one dose won’t cut it. Roughly 8–12% of cases need multiple epinephrine doses. Keep calm, repeat the IM dose every 5-15 minutes as needed, and administer oxygen and intravenous fluids for hypotension as per your standard operating procedures or local protocols. Patients on beta-blockers may need glucagon — something to discuss with medical control if you have it[1].

Treatment and Supportive Care: Positioning, Airway, Oxygen, and IV Access

Position of comfort: If the patient is alert, help them find a position that eases breathing without compromising airway patency—typically sitting upright or semi-reclined.

If unresponsive or unable to maintain position: Lay the patient flat on their back or in the recovery position and have suction ready to clear the airway of secretions or vomitus that threaten patency.

Oxygen administration: For alert patients with respiratory distress, provide oxygen per protocol. If breathing is inadequate, high-flow oxygen via a non-rebreather mask (NRB) is recommended. Be prepared to assist ventilations with bag-valve mask if respiratory effort deteriorates.

Intravenous access: For ALS providers, establish and maintain circulation with at least one large-bore IV and administer fluids according to local protocols to support blood pressure.Wilderness Evacuation Strategy

When epinephrine is administered, evacuation planning becomes a priority. Decisions should factor in symptom severity, patient medical history, response to treatment, and distance to definitive care.

For patients with severe or worsening symptoms, emergent evacuation via medical helicopter is often necessary.

In ground transport scenarios, consider requesting an ALS rendezvous to provide advanced care during transit.

Always have a contingency plan for managing patient deterioration during evacuation. This includes preparations if the primary evacuation method fails, such as weather-related helicopter grounding or difficult terrain delaying transport.

Wilderness first responders and EMTs should consult medical direction early for prolonged field care guidance, especially when evacuation delays are anticipated.

Robust evacuation strategies and contingency planning enhance patient safety in the dynamic wilderness environment.

Wilderness Medical Kit and Medication Considerations

Out in the backcountry, your medication kit needs to be more robust than what you’d carry in urban settings. The Wilderness Medical Society recommends carrying at least three times the usual urban supply of epinephrine, as biphasic reactions, delayed treatment, or multiple exposures can occur when evacuation times are prolonged[1][12].

Protect your medications from extreme temperature variations as best as possible. While manufacturers recommend storing epinephrine between 20–25°C (68–77°F), recent research indicates short-term exposure to heat, cold, or even freezing may not significantly degrade epinephrine potency[12]. Still, using insulated cases is advisable, especially in hot summers or cold alpine environments.

Don’t forget to stock adjunct medications like antihistamines, inhaled bronchodilators, and corticosteroids for supplementary treatment. When feasible, supplemental oxygen access should be included as part of your evacuation and treatment planning.

Looking ahead, a new needle-free intranasal epinephrine spray (Neffy) was approved in 2024. Delivering 1–2 mg doses without injections, it may transform wilderness care options, but as it is very new, stay updated on availability and guidelines[12].

What About Antihistamines, Steroids, and Inhalers?

These are helpful, but remember: they’re backup players, never substitutes for epinephrine.

Antihistamines (like diphenhydramine) ease itching and rash but don’t save the airway or blood pressure[1].

Corticosteroids may reduce risk of biphasic reactions but take hours to kick in[1].

Inhaled beta-agonists help wheezing, especially if asthma is involved[1].

Don’t waste precious time giving these first or instead of epinephrine.

Wrapping Up: What Every WFR/WEMT Should Remember

Anaphylaxis can strike anyone, anytime, even without prior allergy history.

Recognize it early — rash is common but not required.

Epinephrine IM in the thigh is your first and best tool. Don’t delay.

Train regularly with whatever delivery device you carry. Know how to use it without hesitation.

Secondary treatments help but don’t replace epinephrine.

Evacuate and observe; be alert for symptom recurrence.

Stay current with your training and wilderness medicine guidelines.

Disclaimer

This blog is intended for educational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the guidance of a qualified healthcare provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition or emergency. Wilderness emergencies can be complex — follow your training, local protocols, and consult medical control when possible.

For those wanting to dive deeper, I invite you to check out my Wild Guide Wilderness Medicine courses and comprehensive e-textbook. They cover anaphylaxis and many other critical wilderness emergencies in detail — designed to prepare you to confidently manage whatever the backcountry throws your way.

References

Gaudio FG, et al. Wilderness Medical Society Clinical Practice Guidelines on Anaphylaxis. Wilderness Environ Med. 2022;33(1):75–91.

Lieberman P, et al. Epidemiology of anaphylaxis in the US. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(2):461–7.

Gaudio FG, Lemery J, Johnson D. Recommendations on the use of epinephrine in outdoor education. Wilderness Environ Med. 2010;21(3):185–7.

Carrillo E, Hern HG, Barger J. Prehospital Administration of Epinephrine in Pediatric Anaphylaxis. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2016;20(2):239–44.

Andrew E, Nehme Z, Bernard S, Smith K. Pediatric Anaphylaxis in the Prehospital Setting: Incidence, Characteristics, and Management. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2018;22(4):445–51.

Wood RA, et al. Anaphylaxis in America: the prevalence and characteristics. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014.

Latimer AJ, et al. Syringe Administration of Epinephrine by Emergency Medical Technicians for Anaphylaxis. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2018;22(3):319–25.

Wilderness Medical Society guidelines, Epinephrine use. Wilderness Environ Med. 2014.

Auvi-Q prescribing info.

NAEMSP Position Statement: Use of Epinephrine for Out-of-Hospital Treatment of Anaphylaxis. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2019;23(4):592.

FDA epinephrine storage guidelines.

Gaudio FG, et al. Wilderness Medical Society Clinical Practice Guidelines on Anaphylaxis. Wilderness Environ Med. 2022;33(1):75–91.

WFR vs EMT: Which Certification Will Take Your Outdoor Career Further?

This in-depth guide compares Wilderness First Responder (WFR), Emergency Medical Responder (EMR), Emergency Medical Technician (EMT), and Wilderness EMT (WEMT) certifications to help outdoor professionals choose the right path. It covers scope of practice, training hours, certification bodies, job roles, pros and cons, and recertification requirements. Written from decades of real-world experience in both guiding and EMS, the article provides practical career advice for wilderness guides, ski patrollers, search and rescue members, and other outdoor pros—plus insight into the realities of keeping your skills sharp and maintaining credentials over time.

If you spend your days in the mountains, on the river, or deep in the backcountry, your medical training can be the difference between a smooth rescue and a tragedy. I’ve spent years working both on the road as an EMS provider and in the backcountry teaching wilderness medicine, and I’ve seen how the right course—not just “a” course—can open career doors, build confidence, and give you the judgment you need when things go sideways far from the road.

But here’s the problem: the alphabet soup of medical certifications—WFR, EMR, EMT, WEMT—confuses a lot of smart, motivated people. Then there’s the differences between state certification, national certification, scope of practice, and what hiring agencies actually recognize or list as minimum job requirements.

This guide breaks down the differences in plain language, gives you real-world examples, and shows you how and where each certification can take you—especially when you’re thinking about career opportunities and job placement.

The Big Picture: EMS vs. Wilderness Medicine

Urban EMS certifications like EMR and EMT are built for one goal: stabilize and transport to definitive care quickly. They live in a tightly regulated, state-certified, and nationally standardized world. The EMT is the foundational backbone of the EMS system and the starting point if you want to advance to an Advanced EMT or Paramedic (ALS) certification.

Wilderness certifications like WFR (Wilderness First Responder) exist in the opposite reality: delayed evacuation, limited resources, and a heavy dose of improvisation. There’s no national recognition or federal/state entity that oversees the WFR. In other words, there is no equivalent to the National Registry of EMTs—which is the standardized testing and certification body for EMS providers—so WFR is not legally recognized as a state certification. Instead, WFR standards come from consensus guidelines like those from the Wilderness Medicine Education Collaborative (WMEC) and the Wilderness Medical Society (WMS). The goal of the WMEC and WMS is to provide scope of practice (SOP) recommendations, curriculum content requirements, and guidance on in-person versus online training hours.

And then there’s the hybrid: the Wilderness EMT (WEMT). Same legal standing as a state-certified EMT, but with the depth and improvisational skillset of a WFR. Even if a state doesn’t have specific wilderness-approved protocols, the WEMT still has valuable training in splint building, improvised patient packaging, thorough understanding of prolonged patient care, and wilderness evacuation skills. These capabilities are highly useful even if you’re not working in an official “wilderness EMT” position.

Certification Overviews: Scope, Jobs, Training Hours, and Pros/Cons

Wilderness First Responder (WFR)

Typical Hours: ~70–80 hours

Focus: Delayed care, improvisation, evacuation decision-making, environmental emergencies, long-term patient monitoring

Certification/Testing: Issued by private training organizations, colleges, and universities (e.g., NOLS, SOLO, WMA, Colorado Mountain College, The Wild Guide); not a state certification

Clinical Hours: None required

Common Roles/Jobs: Guides, outdoor educators, SAR volunteers, trip leaders, adventure travel staff

Pros: Tailored to remote settings, excellent for guide work, strong patient assessment training, no CEU affiliation requirement

Cons: If you do not have a medical director to work under (as a guide, for example), you cannot perform specific interventions such as reducing shoulder dislocations and will essentially have to follow the rules of a lay responder or rescuer. This is not a professional-level certification.

Emergency Medical Responder (EMR)

Typical Hours: ~40+ hours

Focus: Immediate lifesaving care until higher-level EMS arrives; basic patient assessment and stabilization. EMRs are typically part of non-transporting agencies.

Certification/Testing: National Registry of EMTs (NREMT) exam; state certification required to practice

Clinical Hours: Often none or minimal, depending on state/local requirements

Common Roles/Jobs: Primarily volunteer or rural fire department first responders and similar positions

Pros: Entry-level state certification, quick to complete, legal authority to provide basic life-saving interventions, works under a medical director as part of an EMS agency

Cons: Very limited scope, minimal career portability, uncommon in wilderness industry

Emergency Medical Technician (EMT)

Typical Hours: ~120–150 hours

Focus: Comprehensive prehospital care, patient assessment, transport, oxygen therapy, basic medications. Some states allow additional modules such as IV therapy that can expand the scope of practice. Must work under medical direction.

Certification/Testing: NREMT exam; state certification required to practice

Clinical Hours: Hospital and/or ambulance ride-alongs required (varies by state)

Common Roles/Jobs: Ambulance crews, ski patrol, fire departments, wildland fire medical units, industrial/remote medics, hospitals, clinics, doctor’s offices, and event medicine

Pros: Widely recognized, opens doors for paid EMS jobs, foundation for advanced certifications, state and national recognition, some ski patrol agencies will offer slight pay increases if you have your EMT certification

Cons: Must maintain CEUs, patient contacts, and agency affiliation; requires clinical rotations for initial certification

Wilderness EMT (WEMT)

Typical Hours: EMT course + ~40–60 hours wilderness module

Focus: Using EMT skills in wilderness, remote, or austere environments, including wilderness improvisation, prolonged care, SAR skills, and expedition medicine

Certification/Testing: NREMT exam for EMT plus a WEMT add-on module (awarded as a separate certification); state EMT certification required to practice EMT skills

Clinical Hours: Same as EMT requirements

Common Roles/Jobs: Ambulance or fire rescue-based WEMT, ski patrol, park rangers, remote industrial/energy sites, REMS (Remote Emergency Medical Support) teams

Special Note: This is really the most basic level you can have if you want to get paid working as a WEMT in wilderness environments because you can be deployed through an ambulance service, fire rescue service, or while being deployed as a WEMT on a REMS team.

Pros: Combines legal EMT scope with advanced wilderness skills, versatile across multiple environments

Cons: Significant time and cost investment; WEMT certification must be recertified every 2–3 years depending on the educational institution. No patient contact requirement for WEMT recertification. Some institutions allow recertification by taking a WFR refresher course.

CEUs and Recertification

WFR

Recert every 2–3 years depending on educational institution policies

Required refresher training hours based on WMEC policy

No patient contact requirement

EMR

Recert cycle varies by state (often every 3 years)

Example: Colorado requires 12 CEU hours; NREMT requires 16 CEU hours

Must maintain affiliation in many states to stay active

EMT

Colorado: Recertification every 3 years (36 hours)

NREMT renewal required every 2 years (20 national, 10 local, 10 individual hours)

Must maintain active agency affiliation for patient contacts

WEMT

EMT certification follows EMT recert requirements above

WEMT add-on module is a separate certification and would need to be recertified every 2–3 years depending on the awarding institution

No patient contact requirement for WEMT recertification

Some institutions allow a WFR refresher to satisfy WEMT renewal requirements

Which Should You Choose?

Choose WFR if…

Your work is in the backcountry, not in urban EMS

You want top-tier delayed-care training without the burden of state certification

You’re not planning on ambulance or hospital work

Choose EMT if…

You want maximum career mobility

You plan to work for EMS, ski patrol, fire, industrial/remote, or event medicine

You’re ready for CEUs, patient contacts, and maintaining an active certification

Choose WEMT if…

You operate in both urban EMS and backcountry rescue

You want a competitive edge for ski patrol, REMS team, or expedition leader roles

You can commit the time and money for full training

Real-World Scenarios

Ski Patrol – EMT or WEMT often required for full medical duties; WFR patrollers may be limited unless authorized by protocols

Volunteer SAR – WFR often sufficient for operational medical roles; EMT/WEMT provides expanded authority and integration with EMS

Adventure Guiding – WFR is standard; EMT/WEMT useful if working with higher-risk or remote expeditions

Final Word

There’s no “one right” certification—it’s about matching the scope of practice to your environment, your career goals, and your schedule. Your other commitments in life will play a big role in determining whether you can take on a longer, more demanding course such as an EMT program, which requires not only classroom and clinical hours but also preparation for national exams.

Whatever you choose, you need to keep your skills sharp. If your primary work is guiding, it’s generally much easier to maintain and recertify as a WFR, since the requirements are simpler and don’t depend on patient contacts. Holding an EMT or WEMT certification as a guide can be more challenging—being a truly skilled EMT requires frequent patient contacts, and you’ll also need to be affiliated with an EMS agency to log those contacts for recertification. Without that ongoing exposure, it’s difficult to keep your EMT skills at their best.

If you’re still unsure which path is right for you, you can reach me through my Colorado Mountain College email address or The Wild Guide email. As someone who has been a wilderness guide for over 30 years and part of the EMS system for over 20 years, I can provide valuable insight and help you make the decision that fits your professional goals and lifestyle.

Blog Post Title Four

It all begins with an idea.

It all begins with an idea. Maybe you want to launch a business. Maybe you want to turn a hobby into something more. Or maybe you have a creative project to share with the world. Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.

Don’t worry about sounding professional. Sound like you. There are over 1.5 billion websites out there, but your story is what’s going to separate this one from the rest. If you read the words back and don’t hear your own voice in your head, that’s a good sign you still have more work to do.

Be clear, be confident and don’t overthink it. The beauty of your story is that it’s going to continue to evolve and your site can evolve with it. Your goal should be to make it feel right for right now. Later will take care of itself. It always does.